My Experience Teaching About Confederate Memorials

Abigail Henry

·

5 minute read

Abigail Henry

·

5 minute read

I am the best teacher when I am sharing something that I am passionate about, find intriguing, or believe is relevant for students of color today. This has been my third year attempting to teach about Confederate memorials, and I feel like I have finally done it successfully. Not perfect, but successful enough. There has been a lot of writing about the removal of Confederate memorials, especially the wonderful work of Clint Smith. However, to my knowledge, there is little guidance on how to teach about these memorials in a high school classroom.

I am always looking for ways to create social studies summative assessments that are not just a benchmark or standardized test. Moreover, I always seek to create out of curricula assignments that are rigorous, engaging, and encourage conversation about race. Many teachers struggle with how to handle or even begin such discussions with their students, especially given the politics around education. Teaching about Confederate memorials provided an opportunity for students to critically engage in a national conversation.

The idea originally came to me over the pain I felt when I encountered the news of the “Unite the Right” rally in Charlottesville. I went to the University of Virginia for my undergraduate degree, and based on my experience, I can’t imagine what it was like for students of color to witness the 21st-century version of a white-supremacist KKK.

The idea came to me again when I rewatched this famous video of a Kansas high school teacher facilitating a discussion about the Confederate flag. I thought to myself, What would have happened if my college roommate hung up the flag when they moved in? This was an engaging question worth asking students of color. It provides the opportunity to consider what their response will be when they encounter a blatant racist act or symbol.

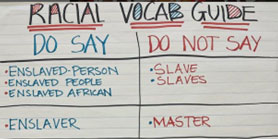

Teaching about Confederate memorials provides teachers the opportunity to not only discuss race and the Civil War. Confederate memorials also provide the opportunity to think deeply about cultural memory, US values, and the untold story of historical artifacts. The figures on our currency matter. What we name our streets and schools matters. The statues we create and the figures we name parks after symbolize what stories in history have been cherished.

I have read a lot about Confederate memorials to prepare the lessons I created, and I still do not feel like an expert. A secondary history teacher can never be an expert on one subject if they have to teach ancient Africa through current issues today, like I do. However, the more I read and listened, I realized the significant issues related to Confederate memorials that my students needed to discuss. The following are the points of interest I chose to illuminate in my lesson plans.

The next time Confederate memorials become headline news or a topic of conversation, please remember the following:

- Most of the Confederate memorials were not installed until many years after the Civil War. I did not know this. I wrongly assumed that Confederate statues and memorials were created within 10–20 years after the Civil War. This is not the case. Their creation surged when racial violence by white-supremacist groups was rampant.

- White women had a significant role in creating the memorials. Too often when we think of or discuss slavery, it’s within discourse about the experience of the enslaved person and the White male enslaver. Yet numerous records show that White women were not just bystanders. They were often complicit in the trauma inflicted on Black individuals. Therefore, after a war in which they lost their husbands, fathers, brothers, and more, it should be no surprise for us that White women were on the front line establishing Confederate memorials as a cultural need. Unfortunately their activism spread elsewhere.

- What is done with the memorial is just as important as when it was historically and culturally created. Confederate memorials were created and installed to send a message about the “lost cause.” They gave cultural power to lynching, Jim Crow mandates, and racialized terrorism.

- The statistics regarding who is memorialized in public monuments are terrible. According to National Geographic, “Among the top 50 individuals commemorated, Confederate leaders outperformed women by four to three. Half of this group of 50 owned enslaved people, and all but six of these were white men.”

- Germany memorializes Jewish people who died in the Holocaust better than the United States considers the African American experience. We should be embarrassed as a country by how much we lack memorials for the trauma, contributions, and joy of the Black experience. This is why the work of Bryan Stevenson and the Legacy Sites of the Equal Justice Initiative is so important.

Here is a general outline of the mini-unit, typically three to five days, that I created to discuss Confederate memorials.

Day 1: Students consider and discuss the purpose of memorials. In addition, they engage with the current record of Confederate memorials, Clint Smith’s work, and a specific example of a memorial removed.

Day 2: Students read and discuss what should be done if a memorial is removed. Should it be placed in a museum? Destroyed? Where should it go? Or should it remain in place?

Day 3: Students write a four-paragraph essay answering the question, “Who should the United States memorialize?” Teachers will review requirements and guidance for success.

I want to highlight that I taught these lessons to Black students in West Philly. I had to modify, add, and adjust a lot for something I felt comfortable publishing. The published lessons and discussions I wrote are not just for Black students at a Title 1 school. They are for everyone.

I also want to elevate the diversity of opinion of my Black students when it comes to Confederate memorials. Too often people think that Black students from an urban school have the same opinion. That’s why letting the statues remain must also be an option in considering what to do with Confederate memorials. I had three or four Black students say they should “remain” because they “don’t care about the statue” and want more “action” on racial inequality. Another student said they should remain so “we should learn from it.” Indeed, as much as I personally want most of them removed, we need some of them to remain—perhaps in a museum—to remember and learn from Confederate memorial history.

Lastly, I want to point out what is not in the lesson plans. They do not include teaching about existing African American memorials. I originally wanted to include them, but it made the plans a little too messy and unfocused. I plan to create a follow-up unit about existing African American memorials, including further explanation of why we need them, and then have students consider what type of memorial they would like to propose and why.

As Clint Smith argues in How the Word Is Passed, “at some point it is no longer a question of whether we can learn this history but whether we have the collective will to reckon with it.”

I’ve included some wonderful student reflections:

“I believe we should recycle those hateful memorials to make ones of people who deserve them. The materials used to make statues of Confederacy should be used to make those of enslaved heroes. The streets named after enslavers should be renamed to those who fought against slavery. The time, effort, and money put into keeping these memorials should be used instead for something the U.S. could be proud of.”

“Many people see these monuments as symbols of racism and oppression, reminding them of a painful chapter in history. The debate over these memorials highlights need to consider the feelings and experience of all Americans and promote a more inclusive understanding of the nation’s past.”

“There are many more memorials of white supremacists, but not many of blacks. This is very sad, over 2,000 Confederate people are being honored for torturing enslaved people. For example, a KKK member Nathan Forrest has a park named after him. … In his biography it states he was responsible for the Fort Pillow Massacre. This man has no right to be memorialized. We shouldn’t memorialize people who harm innocent people.”

Subscribe to our newsletter to download the full lesson plan and slide deck. Additionally, this lesson plan is available with Movement as an additional support to teaching AP African American studies and Black American studies courses.

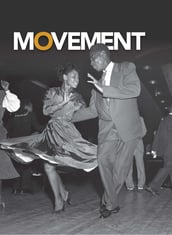

Movement | Black American History

Movement | Black American History

Written and reviewed by Black scholars and experts, Movement, examines the cultural, social, political, and economic contributions, stories, and movements of Black Americans. Offered as both a five-volume series and a beautiful, hardback textbook, Movement highlights the obstacles, triumphs, and cultural contributions of Black Americans who have shaped US history.