Addressing Myths, Stereotypes, and Assumptions

Abigail Henry

·

4 minute read

Abigail Henry

·

4 minute read

This month we are featuring the voice of Abigail Henry, a Black history and studies teacher in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania. She is also a guest contributor to the 1619 Project. Here, she shares a lesson plan that challenges stereotypes about divisions of plantation labor and how these assumptions can affect students’ positive racial identity today.

A Fieldwork Versus Housework Secondary Lesson Plan

Nothing irks my soul more than one of my students saying something like, “That’s cuz you are so light-skinned.” It is derogatory, harmful, and perpetuates stereotypes that developed from the legacy of slavery. For these reasons, my lesson on fieldwork versus housework is an absolute favorite. By addressing myths, stereotypes, and assumptions about the division of work, students are challenged to deeply engage with and think critically about the institution of slavery.

I teach at a Title 1 school in West Philadelphia. This year almost 100 percent of my students are children of color. There are certain things in my classroom that I cannot let slide. Protecting Black identity is not enough for me. One of my goals in teaching Black history to Black students is to encourage positive racial identity. As my mentor, Sharif Elmekki from the Center of Black Educator Development, recently shared with me, “When Malcolm X asks us, who taught you to hate yourself? the answer, unfortunately, too often, is my school’s history teacher did.”

For educators who truly want to support the self-love of students of color, it is incredibly important to be prepared to address issues of colorism that arise in our classroom. The lesson I have developed on fieldwork versus housework is preventive intervention I designed to provide students with an opportunity to learn about divisions created within the Black community.

I recently finished Jarvis Givens’s Fugitive Pedagogy, which is a wonderful guide for decolonizing social studies education. This fugitive lesson could be considered a type of “race vindication” as it provides a means of countering knowledge and misrepresentation of Black identity. Furthermore, this lesson plan spearheads one of LaGarrett King’s “Black Identities” principles of teaching Black history from a Black historical consciousness approach; discussion of fieldwork versus housework encourages a more inclusive history of slavery and uncovers the multiple identities that adapt, change, and persevere under horrific antebellum conditions.

There are many existing myths regarding the division of enslaved labor. The most common is that those who worked in the house were always “lighter skinned” due to rape by the enslaver. In addition, I find that many students wrongly believe that due to the demands of picking cotton, those who worked in the house “definitely had it easier.”

The discourse of this lesson is rigorous and engaging. Through a series of Think Write Share and discussion questions, students will learn that this could be true, but not always. It is important to point out to students that each plantation was unique. An enslaved person could be dark skinned and work inside the house, and vice versa.

What remained consistent throughout all plantations was the daily oppression, fear of violence, and ongoing resilience of the Black community. Indeed, as Matthew Desmond highlights in the 1619 Project, “plantation owners used a combination of incentives and punishments to squeeze as much as possible out of enslaved workers. Some beaten workers passed out from the pain and woke up vomiting.” Moreover, this terror was not just confined to the field, as Mary Prince details in her narrative: “The next morning my mistress set about instructing me in my tasks. She taught me to do all sorts of household work; to wash and bake, pick cotton and wool, and wash floors, and cook. … [S]he caused me to know the exact difference between the smart of the rope, the cart-whip, and the cow-skin, when applied to my naked body by her own cruel hand.” I complicate assumptions about field and house labor by pointing out that the enslaved person inside the house was under constant surveillance due to close proximity to the enslaver. For those enslaved people who worked in the fields, evenings in a hut or cabin provided a limited opportunity for slight separation and temporary relief from the oppressor.

In addition, incorporating short video clips further challenges students to question division in the Black community related to discussions of slavery. A clip from the highly fantasized and fictionalized Django Unchained provides an opportunity to engage students with a stereotypical Uncle Tom, and it sets them up for success in agreeing or disagreeing with Malcolm X’s assertion that the house negro “loves his master.”

The beauty of incorporating Malcolm X’s “Field vs. House Negro” speech into this lesson is that it enriches discussion and extends the lesson. It is important to ensure students understand that Malcolm X’s argument is larger than the title of the speech. He is arguing that there are some Black people who put the needs and desires of white supremacists before their Black community. There is relevance to the Black community today in X’s claim: Are there Black educators not speaking out about the repression of teaching the history of racism? To what extent are Black police officers perpetuating systems of violence against Black Americans? Are those that “make it out” of high-poverty Black neighborhoods abandoning a commitment to reduce the racial wealth gap? Or is Malcolm X’s assertion only more harmful as naming the division causes more division? With the right framing, combined with a teacher’s confidence in teaching about race, students from all backgrounds could benefit from this rich discussion as it challenges white-supremacist discourse. Too often teachers avoid discussions like these out of fear, unwillingness, or lack of experience. Confronting the legacy of fieldwork versus housework is one step toward dismantling white-supremacist curricula within our schools.

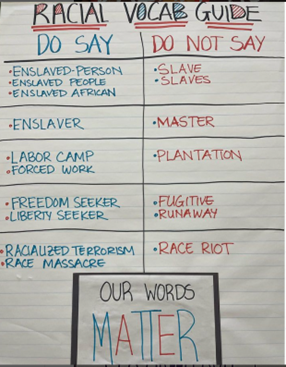

I have a few final suggestions for educators who are considering teaching this lesson. This lesson cannot be taught singularly. This lesson is one component of a unit I wrote for the School District of Philadelphia’s African American history assignment “Development of the Modern World System.” It is part of the story of enslavement. By this point in the lesson students have learned about the beautiful history of Mother Africa, and they have been taught and have had multiple conversations about how to discuss slavery. The words we use to discuss the people who experienced slavery matter. To dismantle white-supremacist educational systems we must be cognizant of our language. Students should know to use the words enslaved people, not slave, and enslaver, not master.

I have a few final suggestions for educators who are considering teaching this lesson. This lesson cannot be taught singularly. This lesson is one component of a unit I wrote for the School District of Philadelphia’s African American history assignment “Development of the Modern World System.” It is part of the story of enslavement. By this point in the lesson students have learned about the beautiful history of Mother Africa, and they have been taught and have had multiple conversations about how to discuss slavery. The words we use to discuss the people who experienced slavery matter. To dismantle white-supremacist educational systems we must be cognizant of our language. Students should know to use the words enslaved people, not slave, and enslaver, not master.

I recently had the opportunity to hear Isabel Wilkerson speak about her books The Warmth of Other Suns and Caste. One statistics that she brought up stuck with me. It will not be until the year 2111 that African Americans will have been free for the same amount of time that they had been enslaved in what is now the United States. For too long, too many classrooms have gone without an in-depth discussion of and consideration about the enslaved experience. We are still way behind in honesty, expertise, and acceptance of teaching Black history appropriately and effectively. I hope this lesson plan is one of many to come in decolonizing Black history.

Subscribe to our newsletter to download the full lesson plan and slide deck. Additionally, this lesson plan is available with Movement as an additional support to teaching AP African American studies and Black American studies courses.

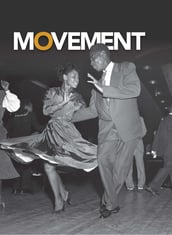

Movement | Black American History

Movement | Black American History

Written and reviewed by Black scholars and experts, Movement, examines the cultural, social, political, and economic contributions, stories, and movements of Black Americans. Offered as both a five-volume series and a beautiful, hardback textbook, Movement highlights the obstacles, triumphs, and cultural contributions of Black Americans who have shaped US history.