Emilie Davis Lesson: A Reflection

Abigail Henry

·

3 minute read

Abigail Henry

·

3 minute read

This month we are featuring the voice of Abigail Henry, a Black history and studies teacher in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania. She is also a guest contributor to the 1619 Project.

Music has always been a significant part of my personal and teacher life. I had a music player in my classroom because music helped with independent work time. I also enjoyed student disagreements over what music to play; it would inevitably lead to a larger conversation about Black music. It is for this reason that Emilie Davis’s diary, her attendance at a Black Swan show in Philadelphia, and my desire to teach more about regular Black folk led to the lesson I created on Emilie Davis.

Music has always been a significant part of my personal and teacher life. I had a music player in my classroom because music helped with independent work time. I also enjoyed student disagreements over what music to play; it would inevitably lead to a larger conversation about Black music. It is for this reason that Emilie Davis’s diary, her attendance at a Black Swan show in Philadelphia, and my desire to teach more about regular Black folk led to the lesson I created on Emilie Davis.

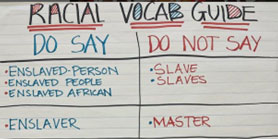

As LaGarrett King asserts in his Black historical consciousness principles, too often, Black histories are learned through the victors or the oppressed experiences of Black victims. This lesson plan provides an opportunity to counter such a Black historical narrative. Emilie Davis was a free Black woman living in Philadelphia during the Civil War. Her insightful diary provides opportunities for Philadelphia students specifically to learn their Black local and social histories. Students in other locations, too, could be inspired by her legacy, and they could then seek out their own local Black histories and narratives. I originally discovered Davis through curriculum work I was doing with Professor Judy Giesburg on Last Seen: The Enduring Search by Formerly Enslaved People to Find Their Lost Families. Our conversations about Black life in Philadelphia during and after the Civil War brought Emilie Davis to my attention. I was immediately captivated as Judy told me about the Black Swan, formerly known as Elizabeth Taylor Greenfield, whose concerts Emilie Davis attended. There was something about her story in which I saw myself, an average Black woman simply trying to live her life and resist anti-Blackness at a grassroots level.

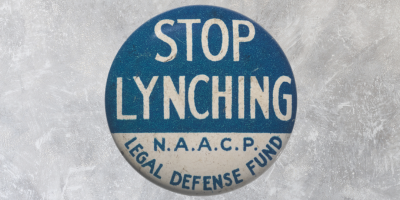

Blair LM Kelley argues in Black Folk: The Roots of the Black Working Class that Black folk have continuously (re)built “vital spaces of resistance, grounded in the secrets that they knew about themselves, about their community, their dignity, and their survival.” I have yet to discover a comparable primary source diary collection as unique as Emilie Davis’s. Davis was in the audience for Frederick Douglass speeches in Philadelphia, went out for ice cream with her friends, made and sold bonnets to raise money for the abolitionist movement, regularly attended church, went to school, and more. Through her diary entries, we gain the perspective of what life was like for a free Black woman supporting the abolitionist movement, trying to educate herself, and also having some fun. Her story allows students to learn about Black humanity from a local female perspective, which is often missing in Black history. Through combining her journal entries with other connected primary sources, we get the perspective of Black participants in the abolitionist movement, illustrating why intersectionality while teaching Black history matters. In addition, we open the doors to Black historical contention as Emilie, despite her support for the abolitionist movement, struggled with her family military service.

In addition, Emilie’s diary reveals the challenges of limited Black freedom in Philadelphia. For example, on September 14, 1865, Emilie Davis wrote in her diary, “i went to hear blind Tom i was much Pleased with the performance excepting we had to sit up stairs which made me furious.” Even this brief entry provides rich content for students discussing the social life of a free Black woman in Philadelphia. How free was Emilie if she could not sit in a musical venue where she wanted? This primary source contains many small, yet significant, glimpses into the life of a free Black woman in Philadelphia during the Civil War. Davis was turned away while getting ice cream, her school was frequently closed, and she witnessed the impact of the war on the City of Brotherly Love, and these were all potential local Black histories I wanted to bring alive for students.

This Emilie Davis lesson focuses on Davis’s thoughts and experiences regarding abolition, Black military service, and social life. Through a jigsaw station activity, students consider Emilie the abolitionist and Black woman in the audience of a Frederick Douglass lecture, her attendance at antislavery meetings, an Ellen Watkins Harper speech, and remarks on the Emancipation Proclamation from a Philadelphia Black preacher. Each of these carefully selected and modified primary sources serve to challenge students to think critically on the experience of an abolitionist Black female audience member.

Despite this lesson including and acknowledging a few well-known Black historical figures, this lesson strives to teach through not the Black social icon, but rather the local Black female as it centers Emilie’s diary and her experiences for discussion. It is my hope that students can learn from Emilie the beauty of keeping a journal, as it is likely Emilie did not know at the time how her individual actions to support the Black collective could impact students like those I served in Philadelphia recently. In addition, I hope all students can learn to create a local space of resistance to support Black people’s dignity and humanity.

Access Abigail’s Emilie Davis PowerPoint lesson (PDF | PPTX) and subscribe to our newsletter to receive her free lesson plan.

Movement: Black American Studies

Movement: Black American Studies

Written and reviewed by Black scholars and experts, Movement, examines the cultural, social, political, and economic contributions, stories, and movements of Black Americans. Movement highlights the obstacles, triumphs, and cultural contributions of Black Americans who have shaped US history.